Green tea – or Camellia sinensis, as it is known in Latin – has been drawing greater attention over the years for its growing list of potential health benefits. Being a tea principally grown in China, naturally part of this is rooted in the history of that country. Some 74% of Chinese tea production, or 927 thousand tons, was dedicated to green tea in 2008, and accounted for an almost equal percentage (76%) of exported tea (229.3 thousand tons) in 2009. Naturally, though, over the years with export, case reports, say, from the United States or Canada found their way into medical journals. These two facts combined have prompted ongoing, systematic studies – both clinical and basic science – to identify and qualify such potential benefits as well as the way in which they may be occurring in the human body.

The primary compounds of green tea, which have drawn the most attention, are flavonoids called polyphenols. In all there are six catechins which have been found, notably EGCG, EGC, EC, ECG, GCG and C1; however, the first two seem particularly connected to not only improving certain conditions but acting in a preventative way too. Additionally, there are three stimulants (methylxanthines) also present in different amounts: caffeine, theobromine and theophylline, the latter two being mild ones.

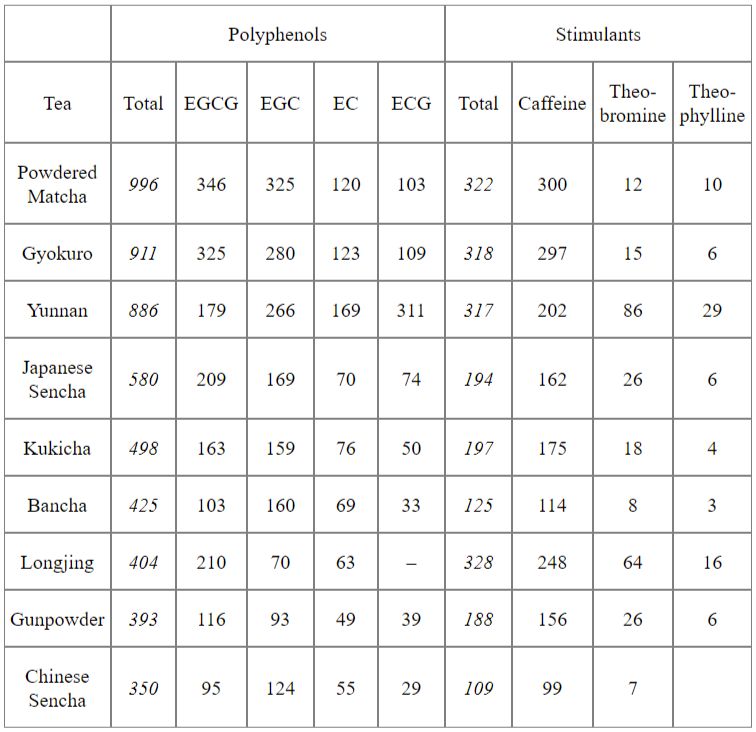

Depending upon the type of green tea and a person’s brewing habits, the concentration of each of these varies:

Values are in mg/L in tea steeped for three minutes in water 80C.

While green tea is sometimes brewed for a second and third time, the concentrations of polyphenols drops markedly: for powdered matcha, it decreases on average for the first cup from 996mg/L to 343mg/L to 247mg/L for the second and third cup; and for loose teas, from 911mg/L to 338mg/L to 297mg/L, respectively.

Perhaps the most well-known health benefit is its anti-cancer properties in connection with the development of certain types of tumors.2 Typically green-tea polyphenols have been found to both decrease cell growth and increase cell death of specific breast, uterine, lung, colorectal, prostate, liver, and oral cancers as well as with leukemia in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, in some cases they were found to improve the effect of certain currently-used or potential chemotherapy agents in a synergistic fashion. Green tea has also been associated with lowering total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels; potentially helping to reduce hypertension but with certain green teas, i.e., Benifuuki; and with a variety of other effects (protective, anti-oxidant; antibacterial, say, with potentiating the effect of oxacillin in the treatment of MRSA; and anti-inflammatory).2

For some predisposed individuals though, a risk to liver health has been reported, leading to a condition of hepatotoxicity. This also been found with some individuals taking large doses of green-tea extract (as opposed to drinking green tea). The number of incidents in the medical literature over the past 10 years, though, has been rare.

Another cautionary note to bear in mind is that, as with other natural health products or foods/functional foods, it is possible that green tea may interact with some prescription medications. Specifically, for those taking:

- Warfarin, it may increase the risk of clotting;

- Simvastatin, it may increase plasma drug levels;

- Cyclosporin, it may increase the effectiveness of the drug; or

- Amoxicillin, it may decrease the effectiveness of the drug.

With a wide selection of green teas from which to choose, a person can satisfy their palate. Now, with a growing body of evidence for potential benefits, one may also help address aspects of one’s health in the process. Surely this is the best of both worlds.